Last week, I argued in favor of the ICRC’s position that if one state uses armed force in the territory of another state then an international armed conflict (IAC) arises between the two states, unless the territorial state consents to that use of force. Accordingly, the treaty and customary law of IAC protects the civilian population of the territorial state as well as the armed forces of the intervening state. For example, on this view, the customary law of IAC applies to US operations in Syria, while Additional Protocol I (to which the US is not a party) applies to UK operations in Syria.

Importantly, the ICRC’s approach applies even if the target of the armed force is an organized armed group operating on the territory—but not under the control—of the territorial state. Accordingly, the treaty and customary law of non-international armed conflict (NIAC) may also apply to such uses of armed force, for example, by governing the targeting and detention of armed group members.

In this post, I’ll respond to some criticisms of the ICRC’s position. Along the way, I’ll make some more general comments on the relationship between the law of force (jus ad bellum) and the law of armed conflict (jus in bello).

Here on Just Security, Sean Watts and Ken Watkin have criticized the ICRC’s position (see here, here, and here). Perhaps the most sustained critique of the ICRC’s position comes from Terry Gill, in a recent article for International Law Studies. There is much to admire in Gill’s article (indeed, I recently assigned it to my students). However, I found his criticisms of the ICRC’s position unpersuasive.

First, Gill rejects “the argument that non-consensual military intervention automatically constitutes a violation of sovereignty and is therefore directed against the territorial State” on the grounds that the intervention may be a lawful exercise of self-defense or may be authorized by the UN Security Council.

This objection seems misdirected. The ICRC does not refer to a violation of sovereignty but instead to an interference or intrusion into the territorial state’s sphere of sovereignty. By definition, a violation of sovereignty is unlawful. In contrast, an interference or intrusion into a state’s sphere of sovereignty may lawful or unlawful. According to the ICRC, an armed interference or intrusion into a state’s sphere of sovereignty—whether lawful or unlawful—will trigger an armed conflict with that state. More on this below.

Second, and relatedly, Gill writes that “there is no reason to assume that the classification of an armed conflict is dependent upon— or even influenced by—the question of whether a violation of the ius ad bellum has occurred.”

This objection also seems misplaced. On the ICRC’s view, the classification of an armed conflict does not depend upon the lawfulness or unlawfulness of the use of force, but instead depends on the fact that force is used by one state on the territory of another without its consent.

Of course, if the territorial state consents to the use of force then (i) the use of force is lawful under the jus ad bellum and (ii) there is no armed conflict between the two states. However, the reason that there is no armed conflict between the states is not that the use of force is lawful but rather that there is no conflict between the states, armed or otherwise. There is no dispute, difference, opposition, or hostile relationship between the two states. Put another way, the fact that consent has been given or withheld is independently relevant to both the jus ad bellum and the jus in bello.

In his second post, Watkin writes that the ICRC’s “reliance on State consent, as the basis for conflict categorization, makes it difficult, if not impossible, to separate it from the law governing the recourse to war.” I respectfully disagree.

The jus ad bellum and the jus in bello are independent in the sense that a use of force may be lawful under one body of law but unlawful under the other. A war of aggression may strictly conform to the law of armed conflict, while a war of self-defense may flagrantly violate the law of armed conflict. At the same time, we do not conflate jus ad bellum andjus in bello simply by recognizing that certain factual circumstances (such as consent or non-consent) may be relevant to both bodies of law.

(For example, if one state exercises effective control over part of the territory of another state then this will ordinarily give rise to a belligerent occupation. Of course, if the territorial state consents then there is no belligerent occupation, not because the occupation is lawful but because there is no belligerency. The same logic applies to the use of armed force and the existence of armed conflict.)

Third, Gill notes that “neither the text of the relevant provisions in the Geneva Conventions (Common Articles 2 and 3) nor the original ICRC commentaries thereto contain any reference to violation of sovereignty as a criterion for determining the character of the armed conflict.” Nor does the ICTY’s Tadić judgment, which Gill rightly describes as “the leading judicial decision on the classification of armed conflicts.”

Since the Geneva Conventions do not tell us when an armed conflict between states exists, we must interpret their terms in light of their context, object, and purpose. The original ICRC commentaries state that “[a]ny difference arising between two States and leading to the intervention of members of the armed forces” gives rise to an armed conflict between those states. It is hard to imagine a more serious difference arising between two States than a difference regarding whether one may use armed force on the territory of the other. If such a difference leads to intervention by the armed forces of either state, then an armed conflict automatically arises.

In Tadić, the ICTY stated that “an armed conflict exists whenever there is a resort to armed force between States.” Importantly, “armed force between States” does not require that two states use armed force against one another but instead requires that one state uses armed force against another.

Now we approach the heart of the matter. What does it mean for one state to use force “against” another? On the ICRC’s view, an armed interference in a state’s sphere of sovereignty is a use of force against that state.

Why invoke the concept of sovereignty in this context? States are legal persons, not physical persons or objects. Strictly speaking, one cannot use physical force against a legal person, such as a state or corporation. One can, however, use physical force against a physical entity—a person, place, or object—over which a legal person has legal rights. There is nothing else that physical force against a legal person could sensibly mean. On this approach, physical force is used against a state when physical force is used against a physical entity within that state’s sphere of sovereignty. There is nothing else that physical force against a state could sensibly mean.

Fourth, and most importantly, Gill identifies several examples involving extraterritorial force targeting armed groups in which “the States concerned [n]either verbally [n]or factually conduct themselves as if they were involved in an armed conflict, even though they may not have consented to the interventions and may have considered them a violation of their sovereignty (irrespective of whether they did constitute such violations).” These examples include military operations by the United States inside Pakistan and Yemen; by Turkey inside Iraq; by Kenya inside Somalia; and by Colombia inside Ecuador.

Admirably, Gill allows that “the lack of hostilities between the intervening and territorial States in these examples may be in whole or in part due to other factors.” But what should we make of the fact that these states may not claim to be in armed conflict with one another? Is the absence of such claims, or the denial of such claims, “subsequent practice in the application of the treaty [in this case, the Geneva Conventions] which establishes the agreement of the parties regarding its interpretation?”

In my view, state silence is inherently ambiguous. Accordingly, we should consider only the explicit legal opinions of states that the law of IAC applies or does not apply. For example, Syria might announce that it is not in an IAC with the UK and that, accordingly, UK forces captured in Syria are not entitled to combatant immunity for acts preceding their capture. The UK would no doubt respond with its own legal opinion, based on its own classification of the conflict and identification of applicable legal rules.

Until subsequent practice establishes the agreement of the parties to the Geneva Conventions (that is, of all states) regarding their interpretation in such cases, we should interpret the terms of the Conventions in light of their object and purpose. As I discussed in my previous post, the object and purpose of the law of IAC is the protection of civilians, civilian objects, and combatants from hostile foreign states. As the ICRC puts it:

it is useful to recall that the population and public property of the territorial State may also be present in areas where the armed group is present and some group members may also be residents or citizens of the territorial State, such that attacks against the armed group will concomitantly affect the local population and the State’s infrastructure. For these reasons and others, it better corresponds to the factual reality to conclude that an international armed conflict arises between the territorial State and the intervening State when force is used on the former’s territory without its consent.

Strangely, in his first post on Just Security, Watkin objects that, by adverting to this factual reality, the ICRC “prioritizes form over substance” because the harm to civilians “may be a mere possibility.” Instead, Watkin suggests that conflict categorization should be based on “an assessment of what actually happens.” On this view, it seems that we will not know what law applies to a use of force until after the use of force is carried out. Among other things, we will not know which legal protections civilians enjoy until it is too late. This seems like an unattractive view.

For his part, Gill acknowledges that “an intervention may impact portions of a State’s population or its national resources,” but writes that

when a population and public property are under the control of an [organized armed group] and not under the effective control of the territorial State, they can no longer be identified with that State for purposes of determining the legal constraints on the conduct of hostilities. In the event the intervening State’s action resulted in occupation of territory, this would change the situation and trigger the regime pertaining to IACs.

Watkin seems to make a similar claim in his first post on Just Security.

Strikingly, Gill provides no support for the first sentence, which is hardly self-evident. Indeed, the first sentence seems to implicitly concede that persons and public property under the effective control of the territorial State can be identified with that State for purposes of conflict classification. Accordingly, if a member of an armed group travels through an area under the effective control of the territorial state then an attack in that area, potentially impacting nearby persons and property, would seem to constitute an attack on the state itself.

Moreover, the second sentence seems to undermine the first. According to Gill, territory under the control of an armed group remains sufficiently identified with the territorial state such that, if the intervening state occupies part of that territory, then an IAC arises between the two states. However, according to Gill, territory under the control of an armed group is not sufficiently identified with the territorial state such that, if the intervening state uses force on that territory, then an IAC arises between the two states. Since control never passes back to the territorial state, it is hard to see the legal or logical basis for this apparently incongruous result.

Finally, Gill observes that “most [academic] authorities take the position that the classification of armed conflicts primarily (but not exclusively) turns on the nature of the parties . . . .” In my view, it begs the question to say that, in the cases under discussion, the two states are not parties to an armed conflict. After all, if the ICRC is correct, then the two states are parties to an armed conflict.

In this post, I have tried to address the most substantial criticisms of the ICRC’s position. No doubt, other objections have been and will be raised. We should expect no less. The controversy that the ICRC’s position has elicited is, perhaps, the best evidence that conflict classification remains highly relevant to the legal regulation of armed conflict.

Professor

Professor  “Between the Law of Force and the Law of Armed Conflict” by

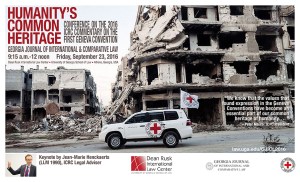

“Between the Law of Force and the Law of Armed Conflict” by  Common Heritage,” our recent conference on the

Common Heritage,” our recent conference on the