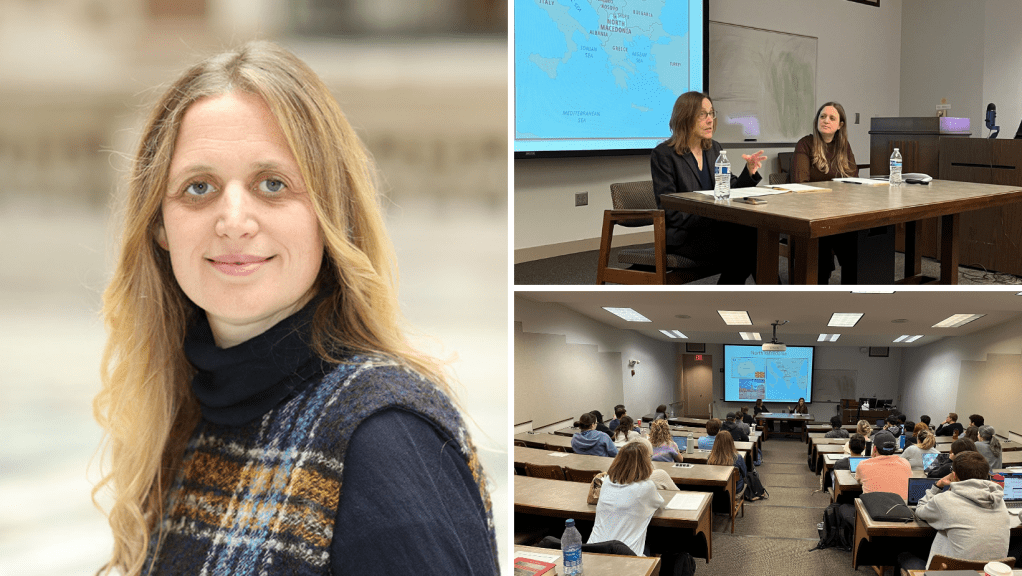

University of Georgia School of Law 2L Madison Graham recently completed an externship in Norfolk, Virginia, in the legal department of HQ SACT, a leading unit of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. This externship forms part of Georgia Law’s D.C. Semester in Practice initiative, in partnership with NATO Allied Command Transformation. Graham arrived at Georgia Law after working as a Staff Assistant and Legislative Correspondent in the U.S. Senate. As an undergraduate at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Graham interned for the USDA in Washington, D.C. Her law school experiences have included service as an Editorial Board Member of the Georgia Journal of International & Comparative Law, a summer internship at Brussels-based law firm Van Bael & Bellis through the Global Externships Overseas initiative, and President of the International Law Society. Below, Graham reflects on her experiences as an extern with NATO HQ SACT this semester.

I first heard about the opportunity to intern with NATO through the University of Georgia School of Law and the Dean Rusk International Law Center nearly three years ago. At the time, I was only beginning to think about law school and where I might apply. Eventually, however, opportunities like this one are the reason I came to Georgia Law. Getting to spend the spring semester in the Office of the Legal Advisor at NATO’s Headquarters Supreme Allied Command Transformation (HQ SACT) was nothing short of a dream come true.

Fortunately, the mere fact of doing the externship is not where the dream ended. Not only was I working in the midst of an international organization, I was also physically working on a section of the biggest naval base in the world. Because of these two features, I received uniquely multifaceted exposure to both the complexities of working in an international organization, as well as the realities of working in a military environment. As a law student interested in pursuing a career in the national security realm of federal public service, this exposure could not have been more valuable.

The substance of the work was also incredibly rewarding. The Office of the Legal Advisor performs an wide variety of legal roles to support HQ SACT’s mission, and I was fortunate to experience parts of each.

First, the office provides legal assistance to the international military staff of HQ SACT. This is usually in the form of helping them obtain local driver licenses, helping their spouses obtain work permits, assisting with traffic tickets, ensuring their visas are up to date, and preparing powers of attorney for outgoing military personnel. Personally, I found this facet of my work to be an incredibly eye-opening and important reminder of how hard it is to legally transition to life in America. But even further, this work involved communicating with NATO staff from each of the 32+ NATO member countries. This was a test of my ability to communicate clearly, anticipate needs and expectations based on certain peoples’ backgrounds, and generally remind myself of how much peoples’ own cultural perceptions affect their approach to life. As an undergraduate anthropology major, I thought I was prepared for this, but could not have expected how much this work experience even further tested and honed these skills for me.

Second, the Office of the Legal Advisor supports HQ SACT through a variety of more general counsel duties. This might include anything from advising on intellectual property rights, contracting, employment law, operational law, and international law. However, the office prides itself on supporting the endeavors of other sections of HQ SACT – ensuring that their plans and processes are within legal possibility. Because of this, the work of the office is largely dependent on the needs and processes of other offices. In my case, this meant I got to help with contracting guidance for contracting officers in the procurement branch, as well as helping to draft another HQ SACT-wide directive for the permissible use of funding for staff morale and welfare activities. This was a great way to hone the knowledge and skills from previous semesters’ contracting and drafting classes, while also having to adapt to the unique requirements NATO has for such documents.

The highlight of my time, however, may have been the multiple educational and coursework opportunities I was able to participate in. These ranged from online, subject-specific courses – on topics like counterterrorism and gender perspectives in armed conflict – to a week-long Strategic Writing Course, to sitting in on meetings with representatives from the International Committee on the Red Cross. Lastly, the Office of the Legal Advisor hosted a week-long Legal Gathering, with legal advisors from several NATO commands around the world invited to talk about each other’s ongoing work and areas in need of assistance. This as a great opportunity to meet other European lawyers with their own unique backgrounds, as well as learn more about NATO’s structure and the roles of each command. Most importantly, however, my supervisors were incredibly supportive of my participation in all these learning opportunities. It is well-understood that just being in the room, taking in as much information as you can, is so valuable to a young student.

Lastly, I was lucky enough to work with incredible colleagues in HQ SACT during my externship. For example, interns from all over Europe, working in other offices at HQ SACT, welcomed me with open arms and have become close friends. I would, however, like to specifically thank my supervisors and colleagues in the Office of the Legal Advisor: Monte DeBoer, Theresa Donahue, Renata Vaisviliene, Cyrille Pison, Kathy Hansen-Nord, Mette Hartov, Agathe Tregarot, and Galateia Gialitaki. Their kindness, patience, and overall support made an already incredible experience even more special. From bi-weekly staff meetings to monthly staff lunches, to staff birthday celebrations, I felt welcomed as a full member of the team from my first day to my last.

I could not be more thankful for my time at NATO HQ SACT, and was reminded of that each time I was asked: “so how do you get to be here?” Over the course of the semester, I must have watched at least a dozen people marvel at the fact that Georgia Law has this externship opportunity available to students. Its uniqueness cannot be understated; I firmly believe it is an something every student at Georgia Law – regardless of your current interests may be – should at least take a moment to appreciate, if not consider doing themselves.

***

For more information and to apply for the NATO Externship, please visit our website.